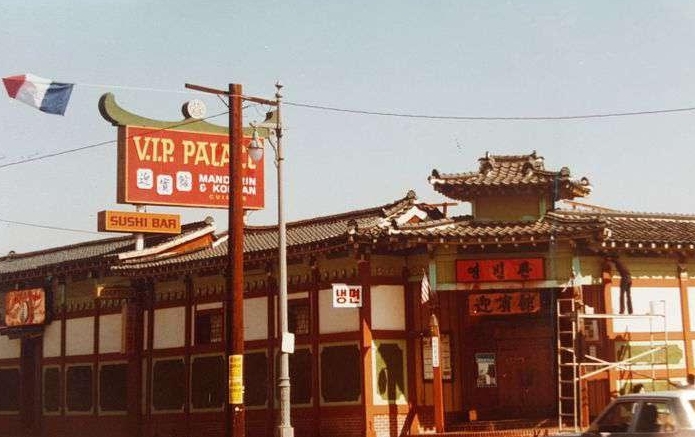

Few realize that before it became home to Oaxacan cuisine, this space served as a crucial gathering spot for the Korean American community. It laid the foundation for what would become Los Angeles’ Koreatown.

The Origins of Koreatown

The history of Koreatown in Los Angeles traces its roots back to the early 20th century. It began with a small but important wave of Korean immigrants who first arrived in the United States in 1903. These early immigrants, escaping Japanese intervention and seeking economic opportunities, initially settled in Hawaii. There, they worked on sugar cane and pineapple plantations.

The work was grueling, and wages were low—about 50 cents a day in the 1920s—prompting many Koreans to seek better opportunities on the mainland. By the early 1900s, a growing number of Korean laborers, diplomats, students, and ginseng merchants began moving to California, eventually creating the first Koreatown in Riverside, approximately 56 miles from Los Angeles.

Riverside offered a promising future for Korean immigrants for several reasons. The city was heavily focused on crop farming, which was considered much easier and better-paying work. Riverside was also one of the wealthiest cities in the United States at the time, boasting one of the first orange farms. These conditions allowed a small Korean community to form around Pachappa Camp, led by Dosan An Chang Ho, a revered independence activist.

Pachappa Camp: The Heart of the First Korean Community

An Chang Ho helped establish a mobile Korean workforce that followed the seasonal harvests of peaches, grapes, and other crops, ensuring year-round employment and income. The money earned was often sent back to Korea to support the burgeoning independence movement, which would eventually lead to the formation of the Korean Provisional Government in 1919.

Pachappa Camp was more than just a workplace and residential area. It was the heart of the first Korean community in the United States. After long days of labor, Korean immigrants would gather to celebrate birthdays, weddings, and hold religious services, creating a tight-knit community that provided both social and spiritual support.

The camp was home to the first Korean Hall, Korean School, and Korean Church in America, laying the foundation for a self-sufficient community bound by shared heritage and purpose. Under An Chang Ho’s leadership, Pachappa Camp became a symbol of resilience and unity, embodying his belief that even the simplest act, such as carefully picking an orange, was a contribution to the greater cause of Korean independence:

Seventy years later, the largest Koreatown outside of Korea would emerge in Los Angeles. This rapid growth was fueled by a combination of socio-economic and political factors that spurred a new wave of Korean immigration. In the 1960s and 1970s, South Korea underwent significant economic development, leading to increased urbanization and the desire for better opportunities abroad. Simultaneously, political turmoil and the aftermath of the Korean War left many Koreans seeking stability and a fresh start in the United States.

Yet, Koreatown’s transformation from a fledgling immigrant neighborhood into a thriving cultural hub was not merely the result of a growing population. It was the vision and efforts of two forgotten individuals: Lee Hi Duk and Kim Gene Hyung.

The Vision of Lee Hi Duk

Hi Duk Lee and his wife-to-be, Kil Ja, in Germany [Photo: Courtesy of the Lee Family]

In the late 1960s, Lee Hi Duk, a former miner and welder, wandered the streets of Los Angeles’ Chinatown. As he observed the bustling community and vibrant cultural presence, he couldn’t help but wonder why Koreans didn’t have a similar enclave—a place where their culture, language, and traditions could thrive.

This question lingered in his mind until 1970 when he made a bold decision that would forever change the landscape of Los Angeles. Lee Hi Duk purchased a small store on Olympic Boulevard from a Japanese American owner and transformed it into the “Olympic Market.” It was the first Korean-owned business on the street, offering a variety of Korean foods—rice, ramyeon, vegetables, and meat—all locally produced. The market quickly became a hub for Korean immigrants, offering them a taste of home and a place to connect with others in their

community.

But Lee Hi Duk’s vision didn’t stop there. He went on to establish “Young Bin Kwan,”, also known as V.I.P. Palace, a traditional Korean restaurant that also served as a nightclub and cultural center. This space became a cornerstone of Koreatown, hosting weddings, reunions, and political fundraisers. Lee Hi Duk even traveled back to Korea to bring 10,000 pieces of blue porcelain pottery and invited a skilled craftsman to create the traditional Korean architecture that defined the restaurant. Today, the building that once housed Young Bin Kwan is home to Guelaguetza, but the traditional framework and giwa roof remain.

The Advocacy of Kim Gene Hyung

Koreatown founder Gene Kim (center) with LA Mayor Tom Bradley (left) as the Grand Marshal of the Korean Parade and LA County Supervisor James Hahn as the Honorary Grand Marshal in 1975. [Photo: courtesy of Gene Kim]

While Lee Hi Duk laid the groundwork for Koreatown’s physical and cultural presence, Kim Gene Hyung was instrumental in solidifying its identity. Inspired by Chinatown’s visibility, Kim Gene Hyung launched a campaign to have Korean-language signs and billboards placed throughout the area. At the time, everything in Koreatown was in English, making it difficult for the growing Korean population to navigate their neighborhood.

Kim Gene Hyung’s efforts were tireless. He visited countless stores, even those not owned by Koreans, to persuade them to change their signs to Korean. Within two months, 61 store signs were transformed, marking a significant shift in the neighborhood’s identity.

But Kim Gene Hyung didn’t stop there; he also petitioned the LA City Council to officially recognize Koreatown by its name. After years of persistence, his efforts were rewarded on December 8, 1980, when Los Angeles officially acknowledged Koreatown.

To further solidify Koreatown’s presence, Kim Gene Hyung organized the installation of signs at major intersections, including the iconic one at Olympic Boulevard, marking the boundaries of Koreatown. These signs served as a proud declaration of the community’s presence and resilience, ensuring that Koreatown would be seen and recognized by all who passed through.

The unveiling of the Koreatown sign after Koreatown was officially designated a neighborhood by Los Angeles County. [Photo: courtesy of KORE LIMINTED]

A Legacy in Transition

From its earliest days as a modest market and restaurant to its current status as a thriving cultural and commercial hub, Koreatown has seen it all—the LA Riots, peace rallies, and the celebration of the 1988 Seoul Olympics, which brought newfound pride and visibility to the Korean American community. The building that is now Guelaguetza has stood as a silent witness to these events, its walls echoing with the history that has shaped Koreatown.

Today, Guelaguetza is a well-known Oaxacan restaurant owned by a family that has infused it with the vibrant flavors and traditions of Oaxaca. Yet, beneath the colorful murals and the lively atmosphere, the traditional Korean giwa roof and the enduring framework remain, whispering to its visitors of what this space once was.

The building still carries the spirit of Lee Hi Duk’s vision and the determination of Kim Gene Hyung, standing as a bridge between past and present, between cultures and communities. It’s a reminder that while Koreatown continues to evolve, the roots laid down by its forgotten founders still run deep, shaping the neighborhood in ways that are both visible and unseen.

![]() <Student Reporter Lauren Lee>laurenlee0808@gmail.com

<Student Reporter Lauren Lee>laurenlee0808@gmail.com

Lauren Lee is a Senior student in The Science Academy STEM Magnet